Karen R. Bottar, Ph.D., Director of Fixed Income & Managing Director

The U.S. has experienced a long period of very low interest rates, which were constructed by the Federal Reserve to help pull the economy out of the great recession of 2008-2009. Yields across the maturity spectrum are low relative to expectations for economic growth, inflation and monetary policy. Many investors have increasingly abandoned credit quality criteria, liquidity, and duration parameters, stretching for yield in bonds. This situation takes on added importance today with the Federal Reserve signaling to financial markets its intent to begin “implementing its balance sheet normalization program”¹, meaning it will start decreasing the reinvestment of principal payments on agency debt and mortgage-backed securities carried on the balance sheet. This process is expected to commence in September.

Issuers of corporate debt have been a major beneficiary of these low rates. Corporations have been able to sell a seemingly endless dollar volume of debt, with those corporations of low quality issuing in size and with very few covenant protections for the debt holder. AT&T is a recent example of a “size” issuer. The company sold $22.5 billion in a new offering (to pay for its acquisition of Time Warner) and received offers to buy off roughly three times the amount it wanted to borrow. This offering included $7.5 billion (a third of the total borrowed) maturing in excess of 30 years (2050 and 2058). The company’s total debt outstanding is now $164 billion. AT&T was able to issue long maturity debt at historically low yields relative to risk free U.S. Treasuries. The low level of Treasury benchmark rates should give one pause before buying a bond with a yield of just 240 basis points above a 30-year Treasury. The duration of this bond is almost 17, meaning a one percentage point increase in interest rates would cause a 17 point decline in the price of the bond. Is that sufficient protection in an environment where the Fed has the intent to reduce the size of the balance sheet (currently $4.5 Trillion)?

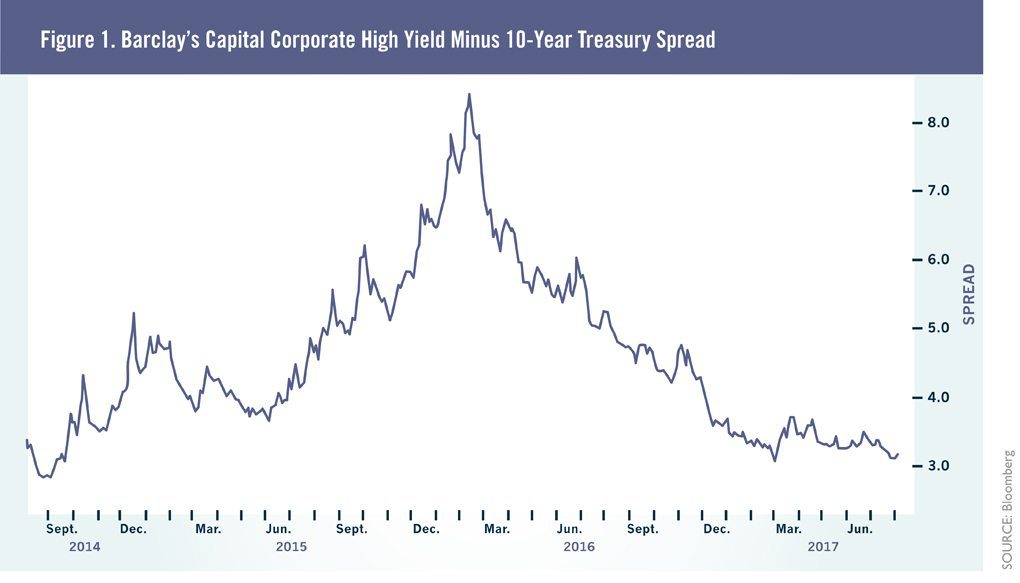

The larger question is whether investors are too complacent about the risks in the bond market. Does anyone really believe a Treasury benchmark of 2.25% for a ten-year maturity which equates to a real (after inflation) return of 0.66% is a good investment value? Does anyone really believe that a spread of 315 basis points for a high yield (high risk) debt compensates investors for risk? We think not. Credit spreads for high yield debt are unusually narrow (see Figure 1 above).

We see several troublesome signs that at this point are just whispers, but investors should listen and pay attention. In one recent example reported in the Wall Street Journal, Santander Bank, a subprime lender, disclosed for the second quarter 9.3% of loans were overdue 31-60 days and that 4.7% were overdue longer than that. In the first quarter it reported 7.3% and 3.8% were overdue for those same time frames.

A second “whisper” is found in an August 4, 2017 Wall Street Journal article, titled “Bond Upgrades Help Commodities Firms”. The article reported on the volume of commodity related borrowers that have been moved from the high yield benchmarks to investment grade. Bonds that were overwhelmingly from the energy and basic-materials businesses (85%). Oil prices are up from the early 2016 lows (when they reached $26 per barrel) with a recent price of $49. Many of these same issuers had their debt moved to high yield benchmarks during the lows in oil prices. Do we believe the risk of these borrowers has been significantly reduced? The Organization of the Petroleum Export Companies is discussing (again) ways to increase production as they need oil revenues.

Rates have been low for so long many investors think this is a permanent environment. There are arguments for demographics weighing on consumption and keeping GDP growth lower for longer and there is a connection between demographics and low inflationary pressures. The reach for yield, however, has compressed spreads across the credit spectrum and encouraged issuance of very long maturity debt. Can this go on forever? History suggests little does. When risk and prices increase prudent investors take notice. Calling the end to a cycle is not our goal. Rather, we need to remind ourselves that a posture of modest duration and high quality is relevant and appropriate, particularly in the face of coming policy changes by the Federal Reserve. The insatiable appetite for yield has led many investors to increase risk to in appropriate levels, which will end badly; it always does.

¹July 26 Federal Reserve Open Market Committee meeting

Market Commentary Disclaimer: This publication is for informational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. The information contained herein is the opinion of Boston Financial Management and is subject to change at any time based upon unforeseen events or market conditions.